By the end of the 15th century, England had become the major manufacturing commercial power in Europe because of the growth in the cloth industry. Rather than collect money from exporting wool and then have importers pay to have it fashioned into cloth, England began producing and exporting woolen cloth. The increase in wool production brought England to the forefront of European commerce. This shift from using the land for growing crops to raising sheep rapidly grew and became quite lucrative throughout the late 14th and 15th centuries. This practice was called “enclosure” because sheep were being enclosed on the land for grazing. Second, nobles stopped growing crops and used the land for grazing sheep to produce wool. By 1500, practically all land held by nobles was rented out. First, they converted all their property to rented lands. In response to these circumstances, the noble landholders did two things. Food prices also fell due to lower demands. The loss of the villeins caused wage labor costs to rise, incurring great expense to the nobles. Although the villeins were viewed as slaves and bound to the land, many took the opportunity to flee and find better employment. With the shortage of laborers, the nobles became desperate to find people to farm their lands. The Black Death, however, provided an opportunity for villeins to change their dire circumstances.

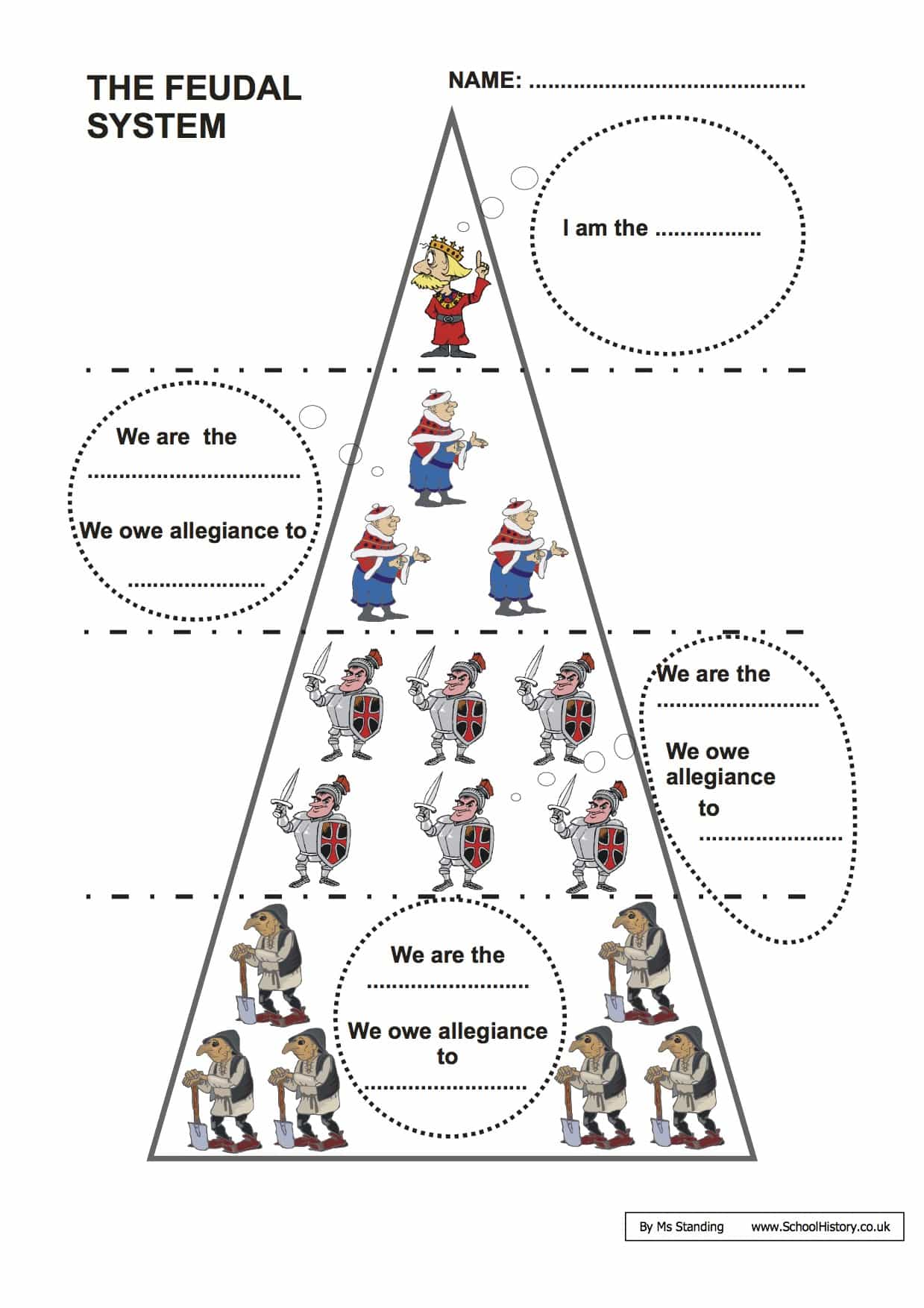

Indeed, the villeins were bound to the land they farmed with little opportunity for improvement in their lives. Annual head taxes were paid, and often the lord would demand revenues whenever extra money was needed. Taxes and numerous fees were also required. Villeins were not only required to pay a portion of their crops as rent, they had to perform duties for the “lord” on a regular basis. The villeins received a very small portion of farmable land, which was often inadequate to grow enough food to meet the needs of their families. These landholders demanded rent from tenants, called serfs or villeins, who ranked lower on the social ladder. Although the king was at the top of the feudal pyramid, his standard of living depended upon the size of the land area that he owned and controlled. The Normans brought with them the feudal system, which depended upon agriculture for success within the hierarchy. Most importantly, great economic changes occurred as a result of the Black Death.įrom the period of Norman rule (1066-1154) until after the Black Death, England’s economy was based entirely on agriculture and the export of some raw materials, including wool. A “commoner” culture with an attitude of sensibility took root and began to exert a great influence over the court and higher culture throughout England. With the loss of so many people, and particularly peasant laborers, labor became highly valued. Nearly everyone who contracted this highly contagious plague died within four days. In 1349, a terrible plague known as the Black Death swept the nation, killing over half of its population. Then there were outbreaks of typhoid fever as well as diseases that affected livestock. This change began in the early 1300s when a great famine wiped out nearly half a million people in England. The growth of the wool industry in England was part of a greater change in which feudalism came to an end and a middle class arose. The manufacturing of wool in England was an important part of European economy in the Middle Ages. The growth of the wool industry led to the expansion of cities, which became centers of trade, manufacturing, and education. Beginning in the 13th century, one of England’s major industries was the production of woolen cloth. Although much of the wool remained in England, merchants were able to export a large quantity of the product. In fact, English wool became well known throughout Europe for its high quality.

In the late Middle Ages more and more farms were dedicated to raising sheep. These peasants raised most of the food that was consumed by the nation.

Throughout the Middle Ages the majority of people living in England worked the land as peasant farmers.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)